|

|

|

|

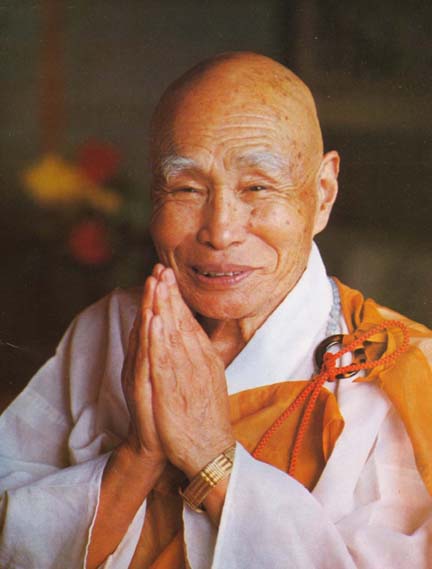

The Most Venerable Nichidatsu Fujii [1885-1985], more commonly known as Guruji, is founder of the Buddhist religious order,

Nipponzan Myohoji, which is dedicated to working for world peace through Peace Walks and the construction of Peace Pagodas.

|

|

|

Born August 6, 1885 in Aso, Kyushu Island, Japan, he became a Buddhist monk at age 19 in opposition to the tendencies of the

time, which strongly encouraged a military career. At age 32, following much study and severe ascetic practice, he arrived

at the realization that his mission--to spread world peace--would be accomplished through the practice of beating a drum and

chanting Na Mu Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo.

Guruji and his disciples have walked through all the continents beating the drum, chanting and offering prayers for peace.

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 marked the dawn of the nuclear age, and Guruji recognized the grave

danger in humanity's new and unprecedented capacity for self-annihilation.

|

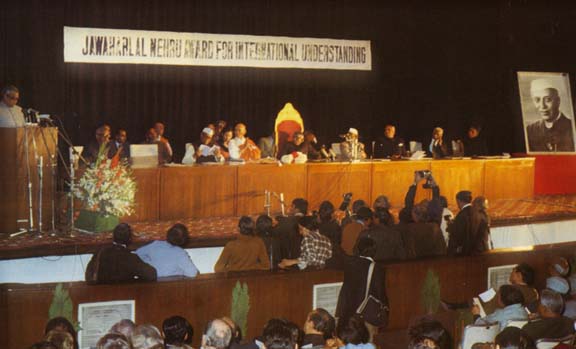

| Guruji accepting the Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Guruji first traveled to India in 1931 to return countless times in the next 52 years. During his pilgrimage and missionary

work in India, he developed deep spiritual ties with the nonviolent independence movement and with Mahatma Gandhi himself

who bestowed the name "Guruji" on him and who took up the practice of drumming and chanting which Gandhi continued

for the rest of his life.

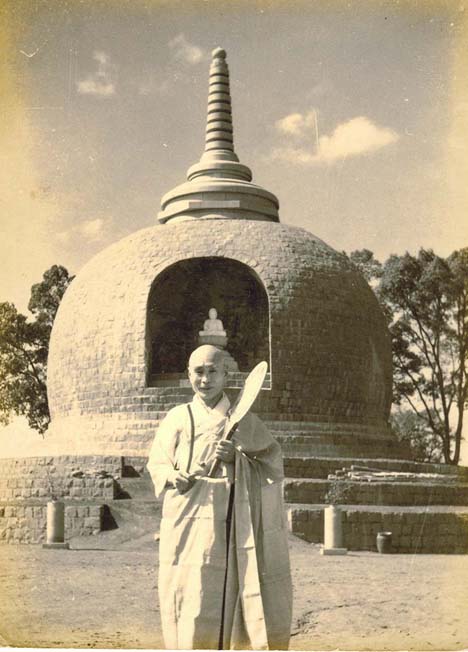

After World War II, Guruji began the construction of Peace Pagodas as a means to build a universal, spiritual foundation

for peace in this world. Peace Pagodas [stupas in Sanskrit] enshrine holy relics of the Buddha. Guruji began building his

first Peace Pagoda in Hanaokayama in Kyushu Island, Japan immediately after the war, offering a new vision and hope not only

amid the deprivation of post-war Japan but to the entire world. Today,Peace Pagodas exist throughout the world and continue

to be built by Nipponzan Myohoji and others in a practice directly from the Lotus Sutra.

|

| Guruji in front of Hanaokayama Peace Pagoda, dedicated in 1952 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Seal Of Fearlessness

I would like to extend my profound appreciation for being favored with the Nehru Award for International Understanding

from India here this day. I reached 95 years of age this year. Reflecting on my long relationship with India, I feel as though

there were no other life for me besides that in India

In the center of Kyushu, located in the

western end of the Japanese archipelago, is the world's greatest volcano called Mount Aso. I was born in a sparsely populated

remote area surrounded by mountains called Sakanashi, a basin that was once a crater of Mount Aso.

Buddhism, which originated in India, was introduced to Japan by way of China and Korea more than 1,400 years ago. Since the

dawn of history, the Japanese believed in an indigenous religion known as Shintoism. Whether or not to accept Buddhism was

deliberated. In due time, Shotoku Taishi [Crown Prince Shotoku] rose and favored Buddhism as the national religion. His Seventeen

Article Constitution proclaimed the national policy of a peaceful nation and declared reverence for the Buddha Dharma a prerequisite

towards that end. Since then, Japan became a nation of Buddhists irrespective of one’s social status. Notwithstanding

the many transitions in the political system, no attempts were made to expel Buddhism during the ensuing 1,300 to 1,400 years.

It was as if the national character of the Japanese people and Buddhism were one and the same and could not be separated.

However, the Meiji Restoration, a political revolution to build a modern state, took place approximately 100 years ago. “Modernization

of the state” was a dominant state policy from Europe to counter the influence of the religious civilization by favoring

a civilization led by science. It culminated in the founding of a communist state. Similarly, the revolution of the Meiji

Restoration in Japan launched a campaign to expel Buddhism, a religion embraced by the people. State-sponsored Shintoism took

its place. Politics and Shintoism were integrated, and the slogan “the unity of church and state” coined. Under

the unity of church and state, the figure at the center of politics inevitably became the essential object of veneration as

the central actor in religious rites. The deification of the Japanese Emperor was the inescapable outcome of the unity of

church and state.

I was born in the 18th year after the Meiji Revolution. It was a time when the

momentum to drive out Buddhism finally took root among the people. Yet, fortunately, since my birthplace is a remote area

nestled in the mountains situated in the western corner of Japan, people still led a life of Buddhist faith. I was fortunate

to be born into a life of Buddhist faith. My relationship with India thus goes back to the times of my ancestors long before

my birth.

There were hardly any sports in my childhood. Life in the country offered no entertainment

throughout the year. I was quite busy helping with farm work even as a child. Recreation was a visit to the temples or attending

celebrations at shrines. We woke with the sunrise every morning and were in bed at sunset. It was life lived with nature.

The impoverished life in the country was a happy life, free from temptations.

By the time of my secondary education, I

gradually awakened to issues of life. To be a politician and ruling the people or to be a general and winning victory are

both seemingly brilliant careers. Yet, their glory is short-lived, their influence limited. On the other hand, religion does

not perish since it is a quest for the eternal. It is also a search for a path that is universally embraced; therefore, it

spreads to the worlds in ten directions. Religion cannot be monopolized by anyone, but is commonly shared by all.

Religion

defines good and evil. It forbids evil and nurtures good. Good and evil are indistinguishable where religion does not exist,

and where good and evil are indistinguishable, life in peace cannot exist. For this reason, we must first seek religious faith

in life.

By the time I completed my secondary education at the age of 17, I aspired to seek the

Dharma and became a bhikshu. That is to say, I became Buddha's disciple and entered a unique way of life detached from ordinary

society. To become Buddha's disciple means to lead a life as the disciple of the World Honored One, Buddha Sakyamuni, the

founder of Buddhism in India, notwithstanding the vast expanse of the ocean and a lapse of 2,500 years. My body was born in

Japan, yet my mind and heart were given birth to in India.

I started reading the sutras after

becoming a bhikshu. In the Lotus Sutra Introductory Chapter I it says, “Thus have I heard. Once the Buddha was staying

at Rajgir on Mount Grdhrakuta with a great assembly of great bhikshus, in all twelve thousand.”

Mount Grdhrakuta

in Rajgir is indeed the mountain where the supreme teaching of humankind was preached, the mountain where the World Honored

One revealed the true purpose for taking birth in this world, the mountain where the religion that emancipates the suffering

of the modern ill world was preached. The Lotus Sutra sets forth:

“I, ever dwelling here,

by my transcendental powers, cause living beings with distorted views, not to see me though I am nearby.”

Although Lord Buddha cannot be seen, the Divine Eagle Peak [Mount Grdhrakuta], the eternal abode of Lord Buddha, still stands

as it did in the past. It was my heart's desire to pay homage to the Divine Eagle Peak, believing in the eternal presence

of Lord Buddha. This is not merely a wish of my own, but one shared by all Japanese people. India and Japan are connected

by Buddhism, and thus are closely tied to each other.

I left Japan and came to India over fifty years ago. I was determined

never to return to Japan and vowed to devote the rest of my life to India. I called this mission of mine Saiten-kaikyo [Returning

the Buddha Dharma to India]. Indeed, I was able to exert myself in my mission centering on India for 50 years since that time.

Joy overwhelms me day and night thinking of the fortune of having become Buddha's disciple.

The

Congress Party, a political organization, was formed in India and planned a political revolution for independence and self-rule.

I was born in Japan the year the Congress Party came into being. I grew up together with the expansion of the Congress Party

movement, and became aware of its activities. In time, Mahatma Gandhiji appeared to lead the Congress’s movement.

In the first half of the present century, political revolutions took place in various countries of the world. Vladimir Ilyich

Lenin of the Soviet Union, Benito Mussolini of Italy, and their like sought to overthrow old forms of government and establish

new political powers. Violence was condoned to achieve that end. India’s revolutionary movement did not rely on military

force or machinery, but on a primitive means of spinning cotton yarn or boiling seawater to produce salt. There is no precedent

in human history of a successful political revolution that overthrew the existing government by spinning cotton or producing

salt. Not a single soul in the world could have even fathomed it. It was deemed to be nothing short of Gandhiji’s daydream.

Gandhiji and his disciples were committed to jail for their crimes of spinning yarn and producing salt. In prison Gandhiji

proclaimed that God’s judgment is near. Gandhiji was pursuing his vision alone in the depth of his “dreamland.”

I was astounded to see pictures of Gandhiji on the Salt March or spinning yarn. I felt I was witnessing something incredible

unfold: at this time of modern scientific civilizations, a genuine revolutionary movement that does not rely on science or

machines, which is, in fact, completely contrary to them, had been launched. Can such a movement overcome the solidly fortified

institution of the modern state and create a different world, a world of nonviolence? Even if it does not succeed, I thought

it to be a fine plan, with extraordinary insight. Spinning yarn or salt making are things even a disciple of the Buddha like

myself can be part of and make a contribution. I decided to immediately leave for India to pray for the success of Gandhiji's

revolutionary movement.

The heaven and earth of India are sacred to Buddhists, the domain of the Tathagata’s eternal

presence. The people of India, believing in the Tathagata's precept of not taking the lives of living beings, were attempting

to apply it to a political revolution. The theater of my religious activities as Buddha's disciple had indeed opened up for

me in India.

Three years had passed since I landed in India. I still had no followers nor had

I been able to meet Gandhiji. For most of that time, Gandhiji and his people were incarcerated. My first opportunity to meet

Gandhiji came on October 4, 1933 at the ashram in Warda. Our meeting lasted only 15 minutes, and there was hardly any time

to speak on matters of substance. We met the following day and the day after that, but unfortunately I could neither speak

English nor Hindi. I therefore submitted an English translation of my views to Gandhiji. This is how it came to pass that

I found residence in the Wardha ashram.

In the meantime, the state of the world was turning ominous. A war between Japan

and China broke out. Its fire gradually expanded. Japan, Germany and Italy concluded a Tripartite Axis Pact that eventually

led to World War II. My country, Japan, was the source of fire. What would become of Japan? I felt it more urgent to prevent

Japan's ruin before I could help in India's freedom movement, and left India alone for Japan.

Upon my return I met with leaders of the army and navy; I ran about battlefronts praying for a peaceful resolution to the

war. However, my effort was in vain. On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allied Forces, which brought an end to World

War II. On August 15, 1947, India had succeeded in the nonviolent revolution and became a free and autonomous nation.

Jawaharlal Nehru became India’s first Prime Minister and visited Japan to console the people of a defeated nation. With

the utmost consideration, he presented an elephant to the children of Japan. In May 1951, the Allied Forces held the International

Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo and executed seven top-level Japanese leaders. Judge Radhabinod Pal of India rendered

a sole dissenting opinion asserting Japan’s innocence.

On September 9, 1951, a Treaty of

Peace was signed. At this conference the representatives from the Allied Forces unanimously accused the Japanese military

of committing a war of aggression. Because of this, India did not send a representative to this conference, and Sri Lanka

stood alone and asked that generous measures be adopted toward Japan in accordance with the teachings of Buddha.

Immediately following independence Indian leaders gathered at the Sanchi Stupa and determined the principle policy of India,

which was to establish a peaceful nation. A resolution was passed to restore Buddhism, a religion of peace, in the interest

of building a peaceful nation. As an initial step to restore Buddhism, a committee to reconstruct Rajgir was organized [1956].

Prime Minister Nehru himself headed the committee and five members were appointed. Despite my being a foreign national, I

became a member of this committee in my capacity as a disciple of the Buddha. The erection of the Rajgir stupa and a stupa

in Kalinga are some of the works by this committee to restore Buddhism. Restoration of Buddhism is not only a spiritual movement

within India, which is requisite to establish a peaceful nation; it is also the most vital spiritual movement in establishing

universal peace in today's world. India’s nonviolent revolution is not merely a mark of her political honor, but a compass

that points towards the future policy of all nations of the world.

The reason for restoring Buddhism

in India and disseminating Buddha’s teachings throughout the world is to bestow the seal of fearlessness on a humanity

menaced by murderous weapons of destruction, capable of repeatedly annihilating life in this saha world.

Fear not, “The various Buddhas and saviors exist with great sovereign, transcendent power and reveal their innumerable

divine powers to please living beings.”

There is a power that destroys this world: it is called the power of machines.

There is a power of the ones who emancipate this world: It is called dai-jintsu-riki [the great, sovereign, transcendent

power]. The power of machines is nothing more than materialistic power. Dai-jintsu-riki is spiritual power. Civilizations

of any age will perish when materialistic power supersedes spiritual power. If humanity hopes to avert its doom, a spiritual

power that surpasses material power must be exerted. The exertion of a spiritual power is preached as kai-butt-chi-ken

[to gain access to the wisdom of the Buddha to comprehend the truth of the Dharma]. The various Buddhas and the World-Honored

Ones appear in the world in order to let living beings, sunk in the sea of suffering, gain Buddha’s wisdom. This is

expounded as the most important cause for which Buddha appeared in the world. The attainment of self-rule and independence

by India is material proof of spiritual power prevailing over material power.

Should humanity

exert its spiritual power in quest of peace and tranquility, nuclear weapons, Trident missiles, space weapons and the like

will not be able to fulfill their role. The precept of not taking life is a solemn precept laid down by the Preceptor, Buddha

Sakyamuni, the World Honored One, in his lifetime. It is the true law of nature, which gives birth to life and nurtures heaven

and earth. No great demon can ever defeat it. Fear not, the seal of fearlessness has already been bestowed in our hands.

Na Mu Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo

January 19, 1979

New Delhi, India

|

|

|

|